Bohemian Lifestyle, Radical Social and Political Activist, Mother, Convert

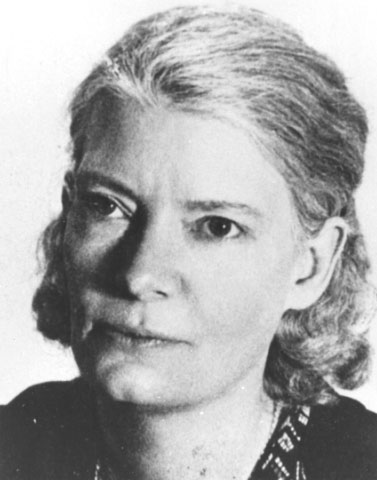

Dorothy Day

Caught up in the loose morals of the time, Dorothy became pregnant and suffered an abortion at the insistence of her partner. This failed to save their relationship, however, which ended unhappily not long before Dorothy attempted to take her own life. Although Dorothy feared that God would punish her with barrenness, light came into her life a few years later through the birth of her daughter Tamar Teresa. Dorothy was then living with the biologist and anarchist Forster Batterham. It was the joys of motherhood that drew Dorothy back to God. She found herself attracted to the Catholic Church, and her desire for eternal happiness for her daughter gave her the courage to seek Baptism for them both. This decision to become a Catholic caused Forster and the majority of Dorothy’s atheist friends to completely abandon and alienate her.

Dorothy struggled to reconcile her newfound faith with her political and social activism. During a visit to the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., Dorothy “offered up a special prayer, a prayer which came with tears and with anguish, that some way would open up for me to use what talents I possessed for my fellow workers, for the poor.” Dorothy’s petition was answered soon afterwards when she met Peter Maurin, a former Christian Brother who had emigrated from France, and through him discovered how to connect her Catholic faith and her desires for radical social reform. Dorothy and Peter together founded the Catholic Worker newspaper in 1933 that promoted Catholic teachings and addressed current social issues. The publication was extremely successful and initiated the Catholic Worker Movement, which opened hospitality houses and farming communes for homeless workers. The movement is comprised of volunteer members who live in community and are focused on the practices of nonviolence, the works of mercy, manual labor, and voluntary poverty. “Our rule is the works of mercy,” said Dorothy Day. “It is the way of sacrifice, worship, [and] a sense of reverence.” Dorothy emphasized the importance of faith as the foundation of all the movement’s good works, stating that, “Food for the body is not enough. There must be food for the soul.”

“The greatest challenge of the day is: how to bring about a revolution of the heart, a revolution which has to start with each one of us?”

At its peak in 1938, the Catholic Worker newspaper had a circulation of 190,000 and the hospitality houses had expanded to include a network of thirty hospices and work farms. Dorothy traveled throughout the world speaking, wrote many articles, and published several books, most notably her autobiography entitled The Long Loneliness. She was known to always carry a Bible, a missal, the Divine Office, and a jar of instant coffee on her numerous trips. Dorothy continued her involvement in protests supporting workers and the poor and participated in fasts against war, asserting that, “The biggest challenge of the day is: how to bring about a revolution of the heart, a revolution that has to start with each one of us.” Dorothy had a great love for the beauty of nature and her small beach cottage on the shore of Staten Island in New York provided her with a place of respite in the midst of her travels.

Dorothy died in 1980 in New York City at Maryhouse, one of the homes she established. Her cause for canonization is now open and the Catholic Worker Movement continues to thrive, with over 200 communities throughout the world. In his recent visit to the United States, Pope Francis cited Dorothy Day as a role model for those involved in social justice and the rights of persons, stating that, “Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints.”